There’s an important cautionary statement in today’s report that — if you go by the headlines — shows that the deaths of 2,000 people a year in Minnesota is attributed to air pollution.

The estimates used in this report carry many uncertainties and should not be taken as exact measures of impacts.

What those uncertainties are exactly we don’t know. But the report — available here — shows “air pollution poses a serious health threat.”

We already knew that, of course. People have respiratory diseases. Air pollution is particularly troublesome for people with respiratory diseases. People die from respiratory diseases. Therefore, air pollution has a role in the deaths of people.

What’s particularly fascinating about the report, however, isn’t the headline-grabbing number of deaths; it’s that it takes less air pollution to cause health problems than apparently it once did.

The report also notes that the quality of air in Minnesota has improved. But we don’t know yet whether there’s been improvement in health as a result of it because today’s report is only for one year — 2008. That provides a benchmark for comparing pollution levels to deaths involving respiratory illnesses, but that’s for the future.

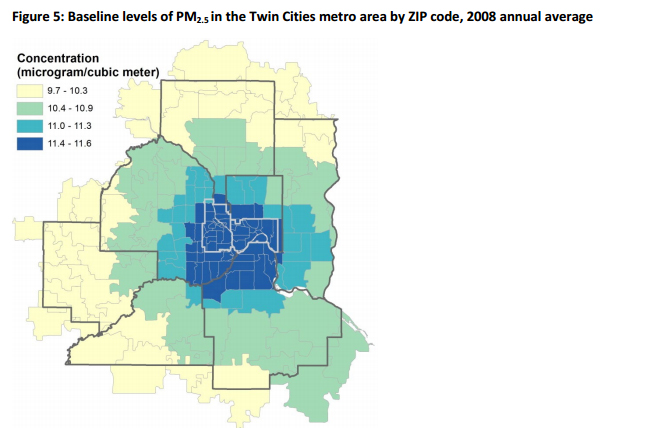

The study also suggests that where the fine particles of pollutants are highest, namely the cities….

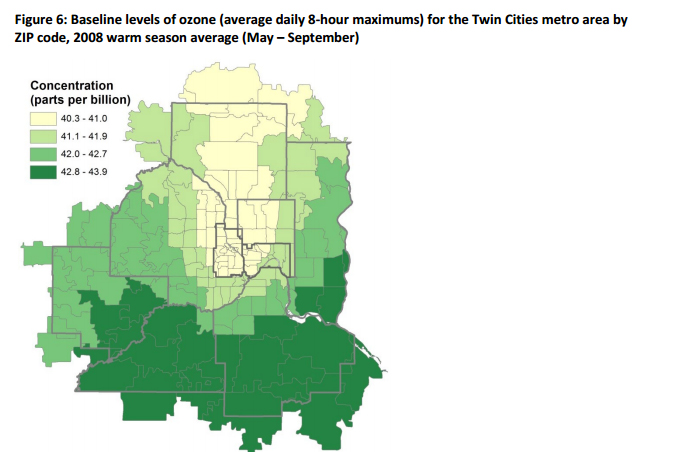

… isn’t where ozone levels are highest.

But that imbalance might not be as “unfair” as it looks since the differences are pretty small.

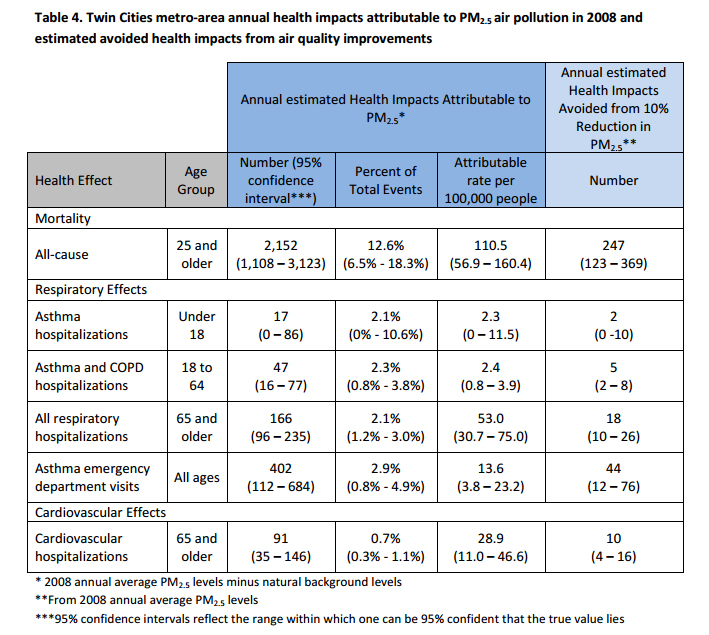

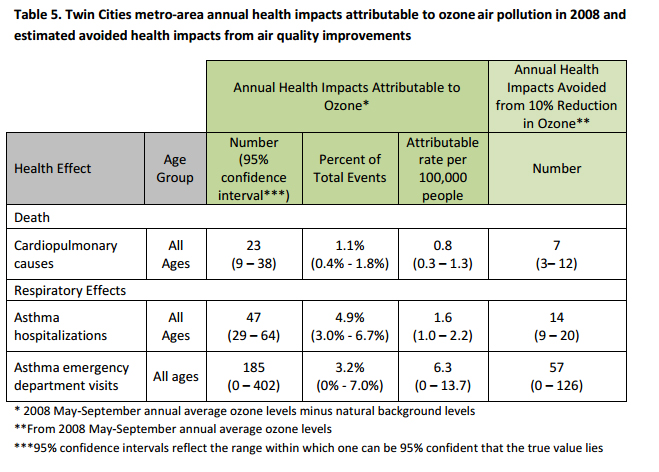

So, could 2,000 deaths be avoided? Probably not. There’s always going to be pollution, there’s always going to be ozone, and there’s always going to be respiratory disease. A fairly sizeable reduction in ozone and fine particles — say, 10 percent — would “save” about 200 people.

Other things would too, of course. A healthier lifestyle and better diet, for example. And there’s that smoking thing.

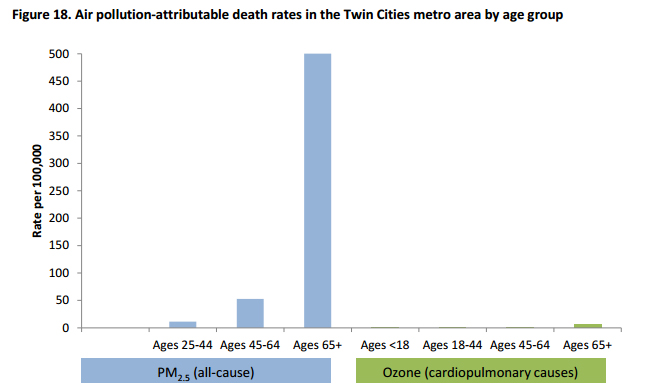

And when you break down the impact to just the Twin Cities, it’s a fairly small number.

That pollution affects the elderly shouldn’t surprise anyone. The elderly death rate is much higher than for younger people, of course.

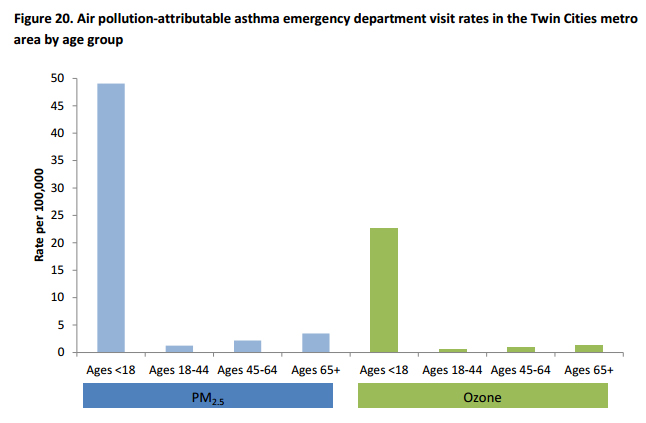

But this chart is particularly alarming — the rate of asthma-related ER visits among the young.

Ground-level ozone pollution in the Twin Cities metro area caused an estimated 23 deaths, 47 hospitalizations for asthma, and 185 emergency department visits for asthma, the report said.

Of course, there’s no telling — at least yet — whether the relationship between pollution and deaths involving underlying health conditions is linear. Would a 10% reduction in air pollution lead to a 10% reduction in deaths? Maybe. Maybe not.

This report, which measures only 2008, won’t be as important as the next one.